"Another snowstorm has flared up, and bygone thoughts are lurking in the dark. Another snowstorm ..."

The cell-phone on the table rang and played a song by Alla Pugachova. "That's right, we also listen to weather music," Nina laughed and answered the call.

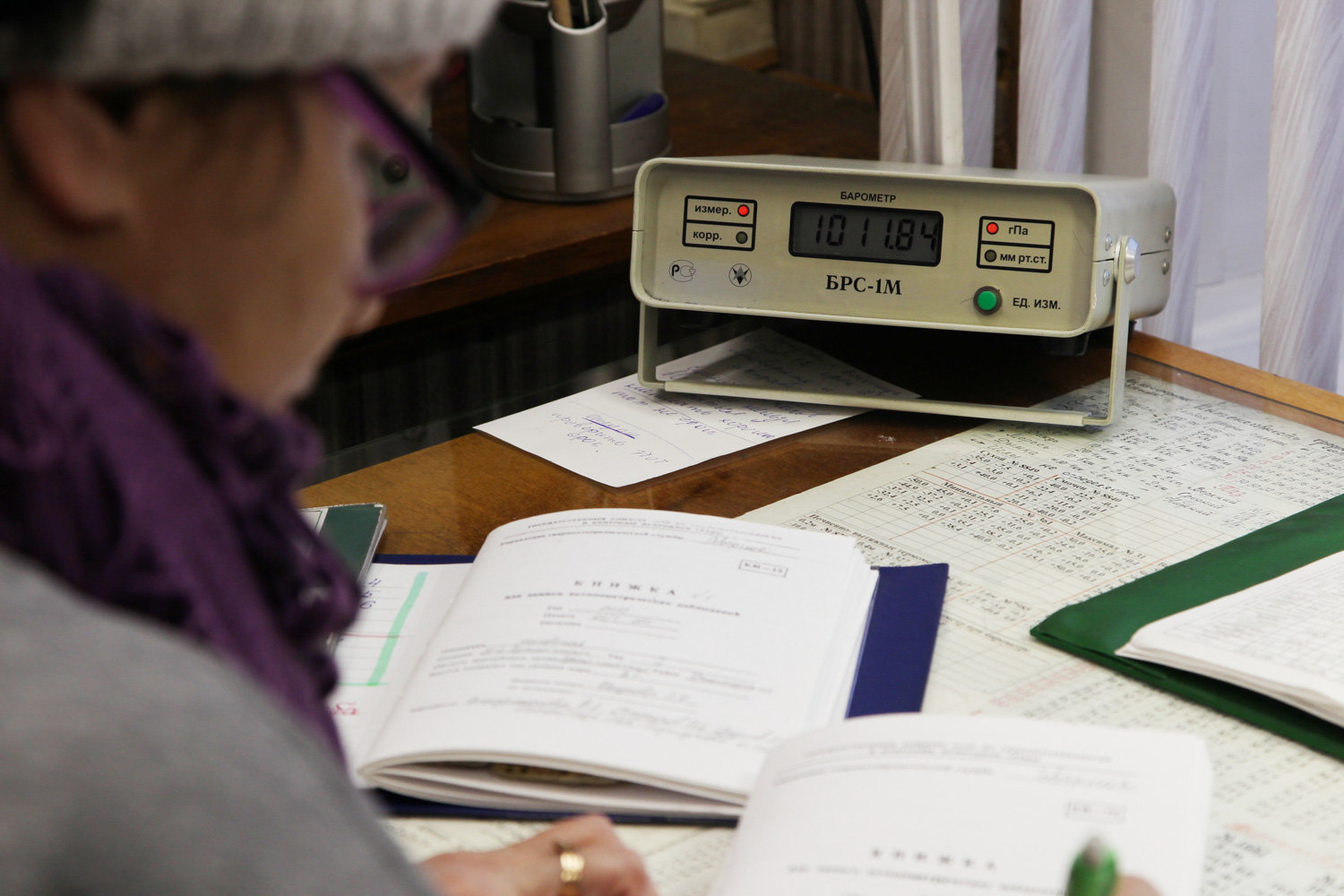

The M-2 Arkhangelsk meteorological station is located inside a small wooden house near a forest, not far from the Yuras River and a gated community for dacha owners.

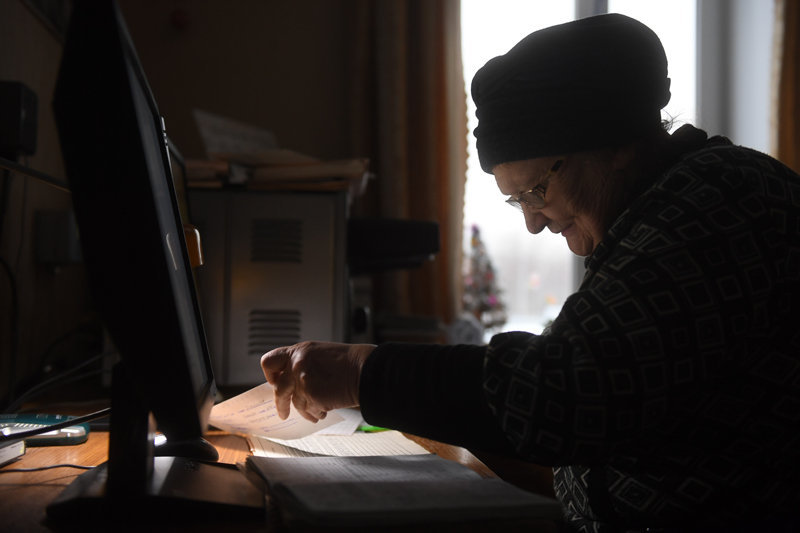

"I don't understand you office people. You spend five days a week and eight hours a day at work. We work day and night and then take a day-off. True, we were hard pressed for personnel a few years ago. Sometimes we had to work for days on end. But we are completely staffed since last fall. Two young specialists have arrived, and we are very happy to have them here. Of course, they make mistakes and slow the performance of our high-quality station...," said Lyubov, head of the station, who looked very much like a school teacher.

She stopped short and waved her hand dismissively. In reality, the specialists relay the station's data every three hours. And the Geneva Secretariat of the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) has awarded an honorary certificate to the station's staff in appreciation of this valuable data.

"It is very hard to work here during the first 12 months," Lyubov noted, emphasizing the word "very." "When I was just starting out, I had trouble dealing with cloud meteorology. Today, young people see discipline as the most difficult thing. You see, no one can deviate from the work schedule. When they tell you to read, you must read, instead of staring at your telephone."