In his diaries, Alexei Tryoshnikov, who headed the North Pole 3 drifting station, writes how polar explorers spent 376 days on the drifting ice-floe and braved atrocious weather and living conditions

In his diaries, Alexei Tryoshnikov, who headed the North Pole 3 drifting station, writes how polar explorers spent 376 days on the drifting ice-floe and braved atrocious weather and living conditions

We departed Leningrad on March 31, 1954. Bright sunlight illuminated the airfield, the snow had melted, and birds were singing. Our families and friends came to see us off. The plane took off and headed due north.

We encountered winter at its peak over Amderma, an Arctic port on the Kara Sea, and we moved closer to the Central Arctic every day

Per tradition, the drifting station chief chooses the ice-floe himself. We spent many hours flying over endless sea-ice formations and hummocks, and we eventually found the most suitable ice floe. We landed safely, pitched a tent and made lunch. After relaxing, we took off again to study the area. We were in no hurry because we would be living and working here for a year. On the following day we landed on our chosen ice-floe once again. We immediately drilled holes and found that the ice floe was three meters thick. This was enough to support a load.

After inspecting the campsite, we decided on a runway for receiving heavier planes and started to smooth it out with spades and shovels. They were our main tools, and we had to use them every day in all four seasons.

The authorities approved the ice-floe; on April 12, it had the following coordinates: 86 degrees, 0 minutes North Latitude and 175 degrees, 54 minutes West Longitude, that is, between Wrangel Island and the North Pole.

The North Pole 3 station team includes experienced polar explorers. Many of them had spent several winters in the Arctic and had taken part in high-latitude expeditions. Some had worked at North Pole 2 station.

The ice floe was barren just a few days ago, and now, on April 16, an entire town had sprung

We put up tents for aerologists, meteorologists, the magnetologist, as well as two others for the radio transceiver and the canteen, and we also built an observatory with snow blocks.

We keep a strict schedule. We eat breakfast, lunch and dinner in two shifts because there were so many people. We agreed not to litter because any paper would accumulate sunlight in the spring, and puddles would start forming around it.

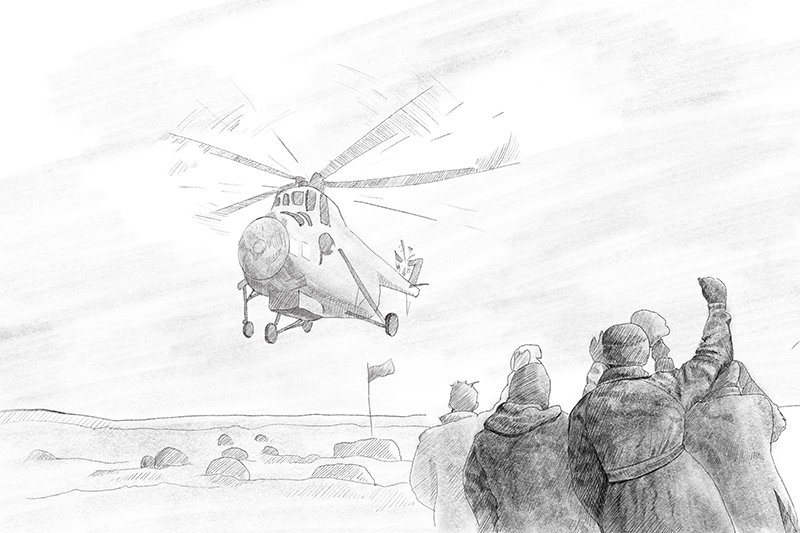

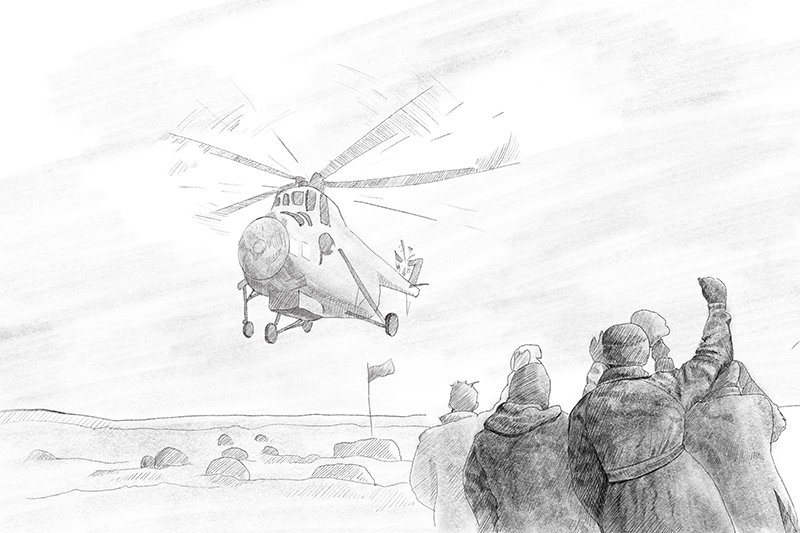

An unusual wingless aircraft with huge rotor blades appeared above the camp. Many of us had never seen a helicopter before. It was strange to watch it hover in midair, fly backward and sidewise and land smoothly on the ice.

This helicopter had flown all the way from Moscow to the Central Arctic for the first time. This was an outstanding event in the history of national aviation. That same day, the helicopter flew over to a nearby airfield where planes had left gas drums and other heavy loads, including a GAZ-69 truck and a disassembled tractor.

Life is already becoming routine; we work at a steady pace, and we are beginning systematic observations

It is late April; everyone is busy with preparations for a May 1 celebration. Flags are being hung in front of the tents, and a snow-block rostrum is in the center of the camp. On May 1, the high-latitude expedition arrives. A meeting took place, then we had a big lunch.

The ice floe is drifting quickly northward, and on May 2 our coordinates were 87 degrees, 11 minutes, seven seconds Northern Latitude and 177 degrees, 34 minutes, three seconds Western Longitude.

Bright sunlight around the clock; there is no difference between night and day. The sun highlights the white-and-blue hummocks ringing the camp. The ice floe is drifting east-southeast. Temperatures in Moscow are now about plus 23 degrees Celsius, but we were cold at minus 20 degrees Celsius.

The polar explorers from Cape Chelyuskin gave us a piano, which was promptly delivered. We put it in the hut and covered it with a tarp

Four prefab homes were also flown in. We quickly assembled them. One houses a radio operator and the sophisticated equipment. Another houses a hydro-chemical laboratory for analyzing seawater samples and hydrologists. We put the two other sheds together and turned them into a mess-room and a galley.

The polar day continues unabated, with constant Sun. The ambient temperature rises fast in May, often reaching zero degrees Celsius. Although the snow melts quickly, it is easy to deal with the extra water in the station's experience.

I kept a diary through our entire voyage, and it provides an insight into our team's life and work during the polar summer. Here are some excerpts:

June 14. The station has been running for two months now. The weather is cloudy, and it snows from time to time. More water is accumulating under the window

June 17. We boarded a helicopter after breakfast and studied the ice situation around the camp. During takeoff, we noticed a thin crack running through our ice floe's northeastern section. People in camp reacted calmly to the news.

June 22. We are drifting west/northwest. A four-engine USSR-N-1139 plane flew overhead at 9 pm. The pilots dropped a pennant with a note, but it fell in a crack and sank.

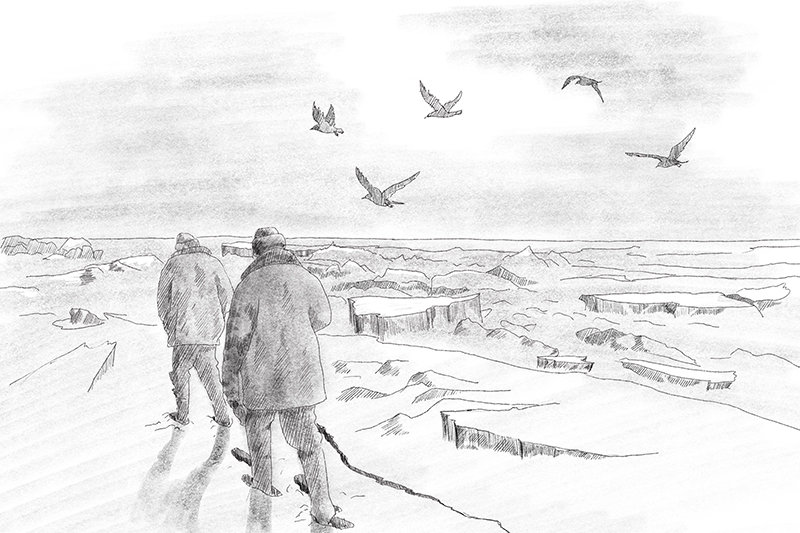

July 5. According to the radio, it was plus 19 degrees in Leningrad yesterday, and plus 26 degrees in Moscow. A hot summer has set in there, but we are being hit by a real blizzard with powerful winds. These winds could spell trouble because we are drifting quickly due south. I saw a small gray bird this afternoon. "A seagull," I shouted, and everyone rushed out to see it. These birds seldom appear in the high latitudes. The powerful wind tossed it from side to side, and it soon vanished in the gray mist, flying northeast.

July 6. In the middle of the day, I saw birds approaching from the south, and we saw that they were ducks.

July 22. Hydrologists scoop up layer after layer of plankton with a small net. The upper levels contain much more plankton, and summer is making itself felt. There are many tiny jellyfish, and we also see microorganisms that give off a bright green light. We have established direct radio communications with Moscow.

August 8. A pilot named Perov landed yesterday. He brought newspapers, magazines, letters and parcels, and also fresh fruit and vegetables. The Gribovskaya vegetable station at the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition [later, VDNKh] sent us melons and watermelons from a place near Moscow, as well as onions, lettuce and radishes. We also received some tapes of the latest concerts. Huge patches of ice-free water up to 500 meters across have appeared around the camp. Our ice floe has turned into an island, and it's a bit unnerving to see so much water everywhere.

August 11. Today we recorded the shallowest depth (1,125 meters) of our entire drift. It is possible that we are over the Lomonosov Ridge. Hydrologists lowered a small trawl in the evening. When they took it out in the morning, high drift speeds caused the cable to hit the ice near the ice-hole's edge. It took us a long time to drag it out. After taking the trawl out of the water, we saw three bright-orange starfish about three centimeters in diameter. Their colors faded once on the surface. We saw many bright and dark spiral-shaped shells.

All of us worship the Sun. Popkov and Minakov wait for hours to see it pop out of the clouds. Helicopter commander Babenko is also watching the sky because it's time to take off and study our situation, but cloudy weather persists

The fog comes in all the time. We spent four and a half hours in midair and had to land in the camp three times to refuel. The last time, we had to turn away just 45 kilometers from the North Pole. We saw tree trunks in four places on the surface of ice floes, and we saw a huge snag floating nearby. We think some Siberian river flowing into the sea brought them here.

On August 25, our ice-floe came closest to the North Pole, drifting just 30 kilometers from it. We crossed the Lomonosov Ridge and observed very pronounced depth fluctuations. In some cases, ocean depths changed from 1,100 to 2,500–3,300 meters over a distance of two to three kilometers. One gets the impression that the ridge is a real underwater mountain chain with its own peaks and valleys.

On September 25, the Sun disappeared behind the horizon for the first time in many months and did not come back for a long time. The polar day is over; the long polar night looms. For several days, the horizon blazed bright at dawn, and dusk eventually set in, growing darker and darker with each day. Stars glowed in the sky during clear weather. A dark night settled in above the ice floe, and we find it more difficult to work.

Planes from coastal bases fly regularly to the drifting station throughout the polar night. They drop off supplies and return for another load. In addition to food and more equipment, the station received five more prefab sheds on sleds.

Each prefab house has furniture and for three or four people. The scientists who specialize in the same field tend to stick together. These homes contain various automatic recorders that have to be adjusted all the time and which don't tolerate the cold very well. Radio receivers were installed all over the camp in the spring. Each tent had its own radio receiver with a loudspeaker, and we regularly listened to radio broadcasts from Moscow and Leningrad with great interest. All houses and work tents had electric lamps all winter long. A powerful lamp and a floodlight were installed at the highest section to illuminate the entire facility.

Planes arrived regularly in the summer and winter, making the station's crew happy each time. Their crews brought letters, newspapers, magazines, books and other things

The polar explorers eat in the mess room, discuss various affairs, relax, play chess, dominos, listened to music and read. We record letters to our families each month, and receive taped letters from Moscow and Leningrad. It's easy to imagine how happy we feel when listening to the voices of our families.

In late August, September, October and November, our ice floe drifted close to the North Pole, moving in loops and zigzags.

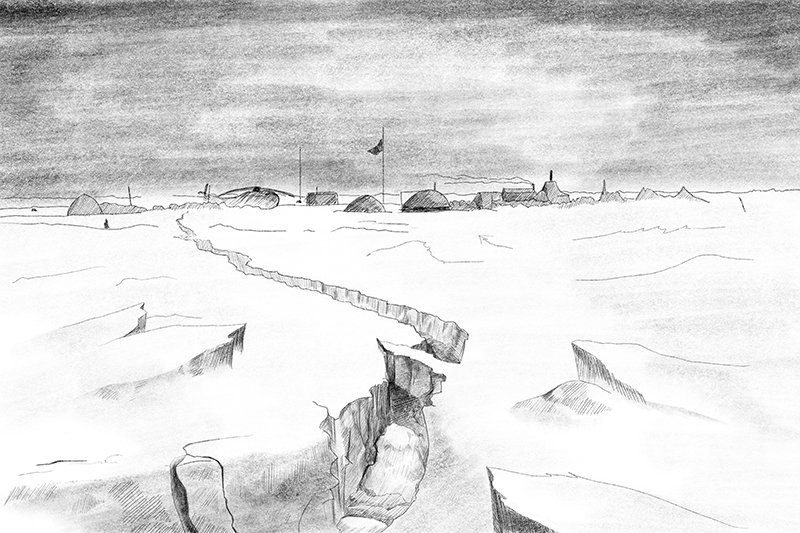

On November 24, a crack ripped the camp apart. The ice-floe shuddered, everyone woke up, ran out of the houses and manned their stations per the ice-alarm scenario.

The crack ran between the houses of the aerologists and meteorologists. Mist rose above the black water surface. The crack ran under a tent with the magnetic-variation station in it, and the edge of the tent hovered over the water. We managed to raise the tent and save the valuable device. The crack separated the aerologists' site from their house. The ice floe's edges drifted apart in 10 to 15 minutes, and the opening was soon about 50 meters wide.

We took off in the helicopter, and turned on its bright searchlight to inspect the camp and the area. We landed on the camp section that had detached. Our comrades stayed here to save their property and move it to a safer place away from the water. A telephone line linked the camp's two sections; the water froze quickly the very next day, and we could walk on it. We also installed a standby radio transceiver in the second area, just to be safe.

Our research projects continued without delay even at that dangerous time. Everyone worked hard but calmly, and there were jokes and laughing

In December, another crack formed perpendicular to the first one, passing under two prefabs and a tent. We could lose our homes and so we used a tractor to pull the houses and tents to another place in the dark and at minus 40 degrees Celsius. A wide area of water engulfed the former camp, and hummocks later formed there.

By late December, the camp's main section was on an ice floe 500 meters long and about 100 meters wide.

On December 30, we received New Year's gifts, letters from our families and a Christmas tree. We had a lot of fun celebrating New Year, and things were calm, although temperatures dropped below minus 40 degrees, and a blizzard swept through the ice-floe. A Christmas tree decorated with multi-color electric lamps stood in the middle of our cozy mess room.

We received endless congratulations throughout early January, and we were very happy to have so many friends and well-wishers.

About 100 days remain until the end of the 12-month observations cycle.

January 2. We are back to work. The hydrologists have started drilling ice-holes in our new camp. It was necessary at last to do so otherwise they had to go to the former camp to take sounding readings.

January 17. We are seeing a full Aurora Polaris for the first time, which probably means that our ice flow is moving south.

January 21. Looks like, it is time to start packing. We are unlikely to complete our 12-month observations cycle. Several ice floes are starting to disintegrate to the south, not far from Greenland. We will cross the 85th Parallel in mid-February, if we continue to drift south at an average speed of 8–9 kilometers.

January 24. We are heading steadily south, averaging about nine kilometers each day. We are tired of the polar night; we haven't seen the Sun for 120 days.

Starting January 25, a dead calm set in, and the ice floe almost stopped moving; we recorded 3,900–3,910-meter depths on those days. All our conversations are about the Sun, which should appear soon, and returning home

February 21. Yatsun from the newsreels studio received a letter reprimanding him for the fact that, in one of his newsreels shot when the ice floe was cracking apart, the explorers looked too happy. But this was true, the jokes and laughing didn't stop during those dangerous moments.

March 14. The Sun rose for the first time four days ago.

March 16. A crack formed under the hydrological tents, expanded to a meter and ripped them from below. We managed to save the essentials, but some minor items were lost. We worked calmly, light heartedly. Yatsun filmed us, and we laughed when his lights explode.

March 28. The crack has started expanding. First, it increased to two meters, and we installed a walkway for the geophysicists and meteorologists to cross to the canteen. I hate to think what would happen if anyone falls into the water. The distance between the snow and the water surface is over 1.5 meters, and it would be very hard to climb out.

March 29. The ice-floe continues to groan and vibrate near the crack: other ice floes are exerting pressure on the "young" ice and compacted snow. All this is happening near our prefab houses, and it appears that the ice floe under them is about to give way. We have to sleep without taking our clothes off.

Today, the Sun did not go down, and the polar day begins

April 1. We will go home pretty soon. But it would be interesting to travel to Antarctica at some point. Despite the fatigue, many of us want to take such an expedition.

April 2. It's midnight but there is plenty of sunlight in our homes; we can read and write without the lamps.

The camp is quiet after a busy day. We can only hear Kurko working in the radio house to send yet another message. A telephone rings every three hours, and an on-duty meteorologist sends a weather report to the radio house. The report is broadcast right away.

We are so far unable to cross the 86th Parallel. It will soon be 12 months since the drift began on the 86th Parallel, but on the other side of the North Pole.

April 3. They told us over the radio the other day that the North Pole 4 station's next tour crew had left Moscow for the Arctic but they said nothing about us.

April 6. The camp's duty officer woke me at 8 am and said the ice floe was disintegrating. At 2 pm, we could see clear water all the way to the horizon to the west and the north from our camp; the crack had increased to 300 meters. Vapor was rising above the water, and ringed seals appeared in the water. We could see nothing but narrow cracks within a 40-kilometer radius the other day, and now we are surrounded by a sea of water. We are in a dire situation.

At 7 pm, we took the helicopter "to the other side" to get some gas tanks. We also took lunch to our comrades working there.

As our station's 12-month drift drew to an end, the ice floes around the camp continued to disintegrate. We had less than 300 kilometers between us and Greenland, and open water stretched south, between Svalbard and Greenland. After landing, the North Pole 5 station crew found themselves on an ice floe north of New Siberian Islands, they arrived to evacuate our team. Each day, the planes airlifted our property to the mainland.

On April 20, 1955, the Soviet flag was lowered at the North Pole 3 drifting station; it had completed its work

Our ice floe traveled over 2,000 kilometers in 376 days, that is, from April 9, 1954 until April 20, 1955, crisscrossing the Arctic in an intricate pattern.

It is hard to single out any member of our team because everyone, from the cook to the station's chief, worked hard and did not spare any strength or energy. The polar pilots did a lot, covering thousands of kilometers to provide us with mail, food, equipment, tools and instruments.

We tried to accomplish our tasks as best as possible and to make our modest contribution to Soviet science.

Excerpts from the chapter Near the North Pole, the Twelve Heroic Feats collection

Hydrometeorological Publishing House, 1964