In early April 1963, the drift participants, polar aviation aircraft and ten tons of cargo were ready to head off to the Arctic. Their goal was to find a suitable multiyear pack ice floe for the station's camp where latitude 76 degrees north crossed longitude 20 degrees west.

The weather was poor for ice reconnaissance with low cloud cover plus fog. The temperature above the ocean did not rise much above minus 28 degrees Сelsius. From the side of the aircraft we could only see black swirls covered in fog. The ice fields were broken up by cracks and hummocks. From up above the ocean looked like an endless floor covered with uneven silvery glazed tiles. After two weeks of exhausting flights we finally found a suitable ice floe.

On the first day we put up a temporary camp on fresh ice. Aircraft were continuously flying in cargo throughout the day and night trying to battle with the blinding sun. Without wearing sunglasses any work was simply out of the question

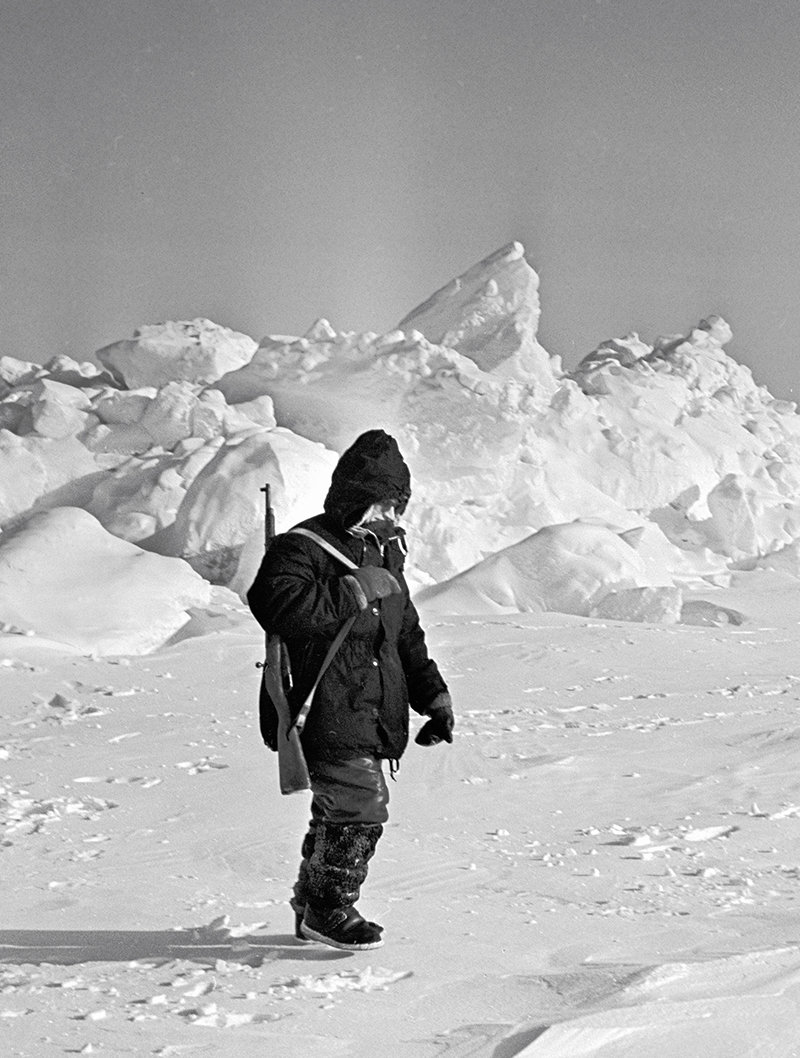

We proceeded to go and take a closer look at the ice floe. It was shaped like a 4 kilometer by 5 kilometer regular ellipse crisscrossed by rows of hummocks of multiyear ice and standing floes rolled smooth by the wind. There were ridges of solid ice underfoot. It was no easy job to walk due to the fact that our high fur boots didn't have a firm grip on the slippery surface. We decided to put up a camp on the slope of a snow-covered smooth ice ridge. It was 5-7 meters high and the ice was 4-6 meters thick.

It took us just two weeks to put up North Pole-12.