For several centuries, Britain consistently sought to expand its trade across the globe. To deliver on this vision, all that was needed was to find a Northwest Passage that would enable ships to sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific by circumventing North America from the north.

The first attempt to find a passage of this kind was undertaken by England back in 1497, and exploration continued for another four centuries. By 1845 the unknown parts of the Canadian Arctic were reduced to a stretch of less than 100 kilometers

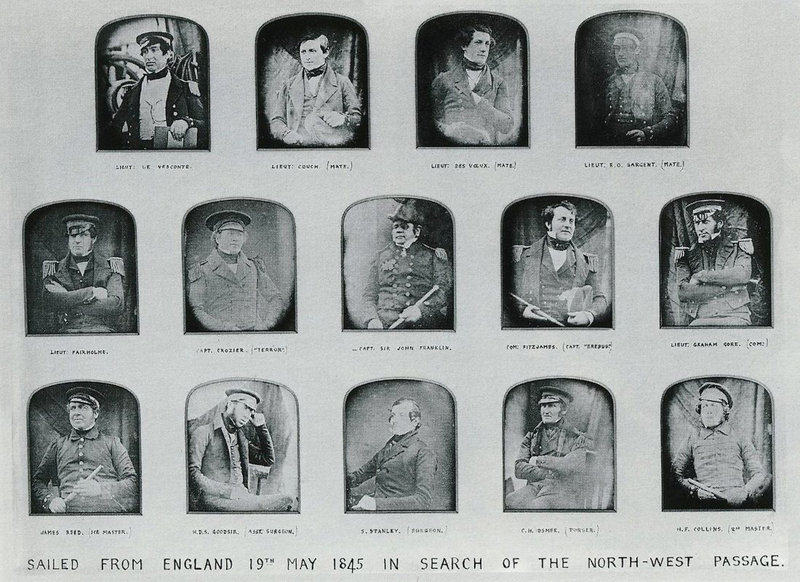

The British Admiralty assigned this mission to John Franklin, a 59-year old captain who had taken part in three Arctic expeditions. Between 1819–1822 he led expeditions to and along the Arctic coast of Canada, during which his crew fell short on provisions, and had to stew up leather shoes, after which he was called the "man who ate his boots." He also explored Alaska and was Governor of Tasmania.

![Reproduction of portrait of British Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin [1786-1847] Reproduction of portrait of British Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin [1786-1847]](https://arctic.ru/images/75/89/758977.jpg)