During the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union was in need of industrial diamonds for use in various machines, including in weapons production. Due to the lack of its own deposits, the Soviet Union had to spend a fortune (money the country desperately needed) to import diamonds. During the war there were neither the physical resources nor the finances to search for diamonds. After the war ended, USSR got on the matter of searching for its own diamond deposits, including geologists whose knowledge and skills could influence the outcome the most.

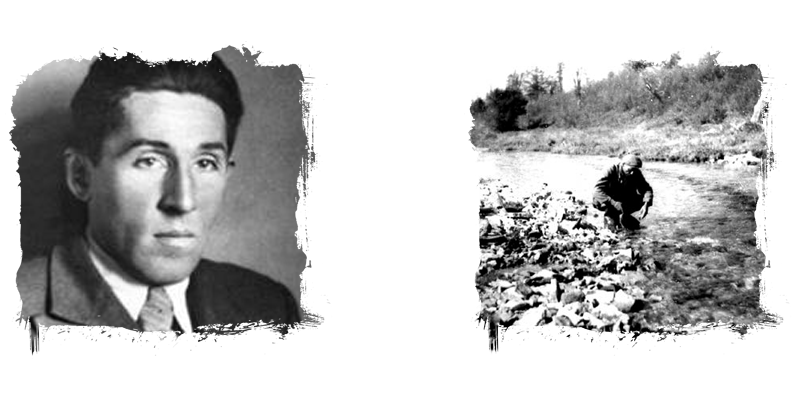

In 1946, geologist Mikhail Shestopalov wrote to Joseph Stalin saying that it was necessary to solve the problem and start looking for primary diamond deposits within the country – specifically, in Yakutia. Earlier, the Amakinskaya Geological Expedition of Union Trust 2 (Main Directorate of Ural and Siberia Geology) had already probed the Siberian Plateau and suggested that kimberlite pipes could be found by tracing the diamonds they had discovered in the tributaries of the Nizhnyaya Tunguska River.

But for many years the search was unsuccessful and cost the country too much