As has already been noted, Tikhaya Bay, the first Soviet polar station that was established in 1929 on Hooker Island in the Franz Josef Land archipelago set out its own code of conduct that had to be observed by all explorers spending the winter season there, regardless of their rank and status. Apart from eating polar bear meat in order to prevent scurvy, there were three other rules:

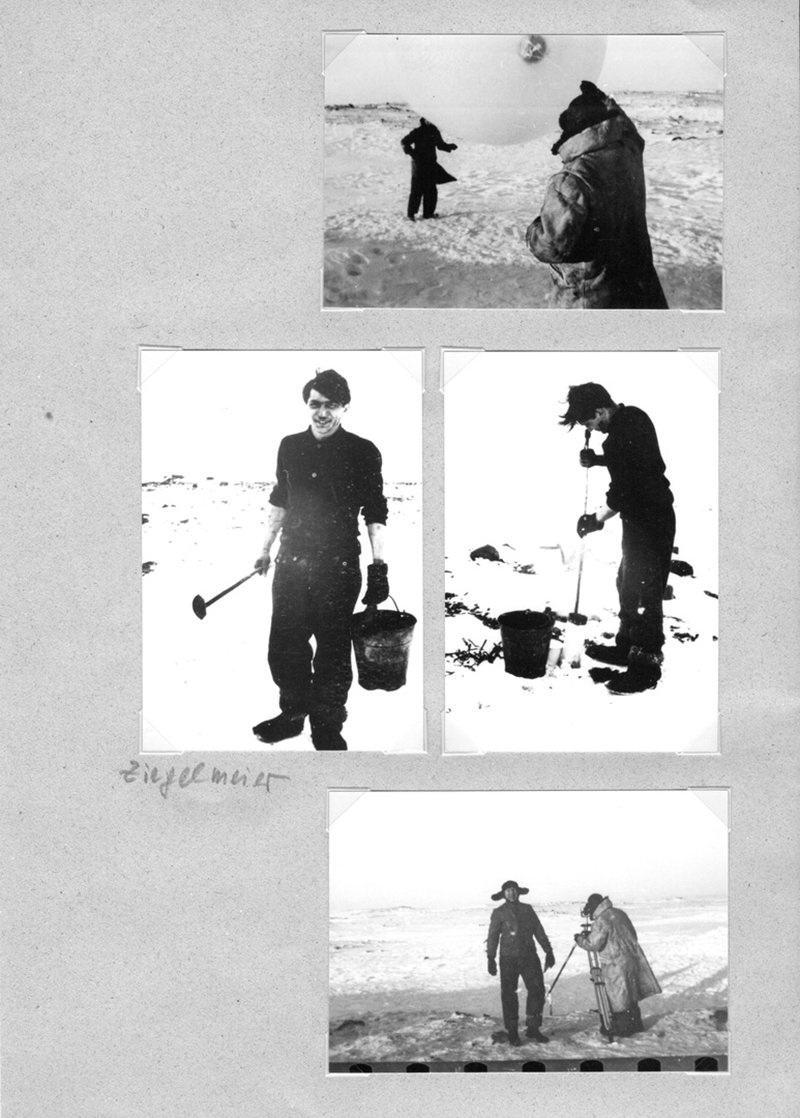

Rule No.1: Do not go near your bed during the day. Rule No.2: Walk or ski around the station for two hours daily in any weather. Rule No.3: Stay inside your room if you are in a bad mood

Many of them broke the third rule after learning that the Germans had sunk a ship carrying a relief crew and food rations for the next year in Kandalaksha Gulf. Now that they had no choice but to spend another winter season at Tikhaya Bay, the members of the station's team decided to conduct an inventory of the remaining food supplies and fuel, and to see which facilities were best suited for life and work. Soon they found out that they were running out of coal for their stoves. They tried to collect driftwood from nearby islands and also decided to divide scarce food rations among all the explorers. And, finally, they eventually dismantled all the buildings and moved into just one building, both living and working there. This is how they obtained enough firewood to last them through the winter season.

Today, researchers still have to unlock many secrets of Arctic exploration, especially from World War II. Many documents have to be found.

The personnel of the Tikhaya Bay station kept an improvised diary called the Blue Book. However, its wartime entries were destroyed for some reason

Researchers rule out any conspiracy theories; this is probably just a vexing coincidence that prevents us from learning more about those difficult and hungry years at the station. The station's crew expected another ship to arrive in 1942, but their hopes were dashed. Planes arrived at Tikhaya Bay two times, delivering the needed equipment, but no food was dropped. However, none of the polar explorers complained or expressed any discontent. Everyone realized that a war was raging and simply did their duty. In fact, their work was of great importance for the nation. The Tikhaya Bay polar station always served as a research outpost for conducting comprehensive hydrometeorological observations. The explorers, who were hard-pressed for food during those two years, communicated regularly with mainland USSR and reported their findings. Just like data from nearby Soviet polar stations, their observations went into an integral database and played a unique role.