Researchers look into the Atlantic’s past to find out the Arctic’s future

The movement of water in the World Ocean can be pictured as an enormous conveyor belt carrying warm surface waters to the north of the Atlantic and on to the Arctic Ocean and returning cold deep waters back to the south. Although the reasons for the accelerated melting of Arctic ice over the recent decades remain a matter of debate, scientists name greater warmth inflow with ocean currents as a possible reason.

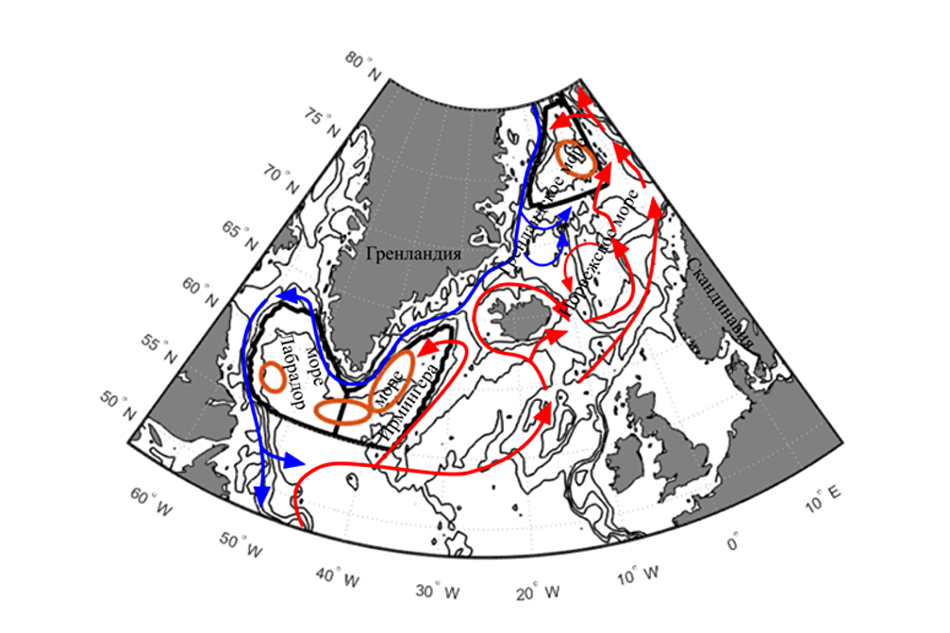

Surface and deep currents are interconnected through deep convection, when surface waters cool down, become denser and sink to the bottom in the Arctic areas. If the ocean supplies more warmth to the atmosphere the process grows more intensive, accelerating the movement of the entire global conveyor. Currently, scientists are aware of four deep convection areas in the North Atlantic: in the Greenland Sea, in the Labrador Sea, in the Irminger Sea as well as between the Labrador and the Irminger seas.

"The dimensions of the convection areas are not large at all by the ocean standards — about 100 km in diameter; moreover, each winter they emerge in different places and at different time. These areas are hard to spot because there are too few oceanographic observations," said Igor Bashmachnikov, an associate professor of Geography at St. Petersburg State University. — "We have more or less dependable observations of the convection intensity only for the recent 10 to 15 years, which is too short a period to determine the direction of climate processes with any certainty."

To solve the problem, oceanologists worked out a new algorithm based on the observation data accumulated since 1950. It enabled them to understand how convection intensity has changed in the three seas over the past 70 years. According to Igor Bashmachnikov, the results were quite surprising. For instance, the Irminger Sea convection, formerly believed to be the least important, turned out to influence the global conveyor's speed and therefore the heat transfer to the Arctic most of all. However, the fast melting of Greenland glaciers, which is much talked about by scientists all over the world, has so far had no substantial impact on deep convection.

"We have also managed to identify convection development cycles about 30 years long," the researcher said. "Such cycles were formerly known by fluctuations of various atmospheric and oceanographic properties, but for the first time they were detected in the changes of deep convection intensity. Now we can see that the warming is slowing down, which may mean that these 30-year cycles are affecting the general trend."

Later, scientists will get down to forecast construction: they will use the same algorithm, but based on the climate models data. "The reasons for the variability of the Arctic climate remain largely obscure," Bashmachnikov explained. "Our work will contribute to understanding the mechanisms of the ongoing climate changes."