The Arctic Council, a high-level intergovernmental forum, promotes cooperation, coordination, and interaction among Arctic states and indigenous peoples. The Arctic Council started functioning in 1996.

In addition to the Arctic state members, the council includes six "permanent participants": the Aleut International Association, the Arctic Athabaskan Council, the Gwich'in Council International, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), and the Saami Council. Representing hundreds of thousands of indigenous people, these groups are concerned primarily with human rights, environmental protection, preservation of traditional ways of life, social and economic development, and education.

Also participating in the AC are over two dozen bodies with official "observer" status. These include several non-Arctic countries; intergovernmental and interparliamentary organizations (such as the World Conservation Union and the United Nations Development Program); and nongovernmental organizations (for example, the International Union for Circumpolar Health and the Northern Forum). Funding for AC programs and projects comes from a diverse array of international sources.

The chairmanships of the council and its six expert groups, as well as the physical location of the AC secretariat, revolve on a periodic basis among the eight member countries. This serves to encourage strong multilateral participation in AC programs. The ministers of the AC states typically convene every year to formally review the projects and reports of the working groups and to respond to the resulting proposals for action.

Several other international forums with regional or broader European interests also address economic, social, and environmental issues that often relate to the Arctic. Notable examples include the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, the Council of the Baltic Sea States, the Northern Forum, the European Commission, the Nordic Council, and the Conference of Parliamentarians of the Arctic Region.

As well, the Northern Dimension (ND)-a policy framework involving European Union states, plus Iceland, Norway, and Russia-assists Arctic/sub-Arctic areas.

Scientists from dozens of universities, government institutions, and other research centers throughout the northern hemisphere have collaborated on a wide range of Arctic studies over the past several decades. One important coordinating body for multidisciplinary research is the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC), which has observer status on the Arctic Council. Comprised of the national science organizations of 19 member countries, the IASC provides advice and some funding for planning and supporting science development.

Another important cooperative network is the University of the Arctic (UArctic), a decentralized association of about 170 universities, colleges, and other organizations dedicated to higher education and research in the Far North. Members share resources, facilities, and expertise to make higher education accessible to students and communities of the Arctic. UArctic partners with indigenous peoples and seeks to engage their perspectives and participation in its activities.

The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) brings together representatives of the various organizations striving to protect human rights of the indigenous peoples living in the Arctic. The IWGIA encourages efforts to strengthen democratic participation by native peoples in the decision-making bodies of Arctic states. Some native groups, supported by IWGIA, seek to establish their own parliaments, similar to the Saami parliaments in Norway and Sweden.

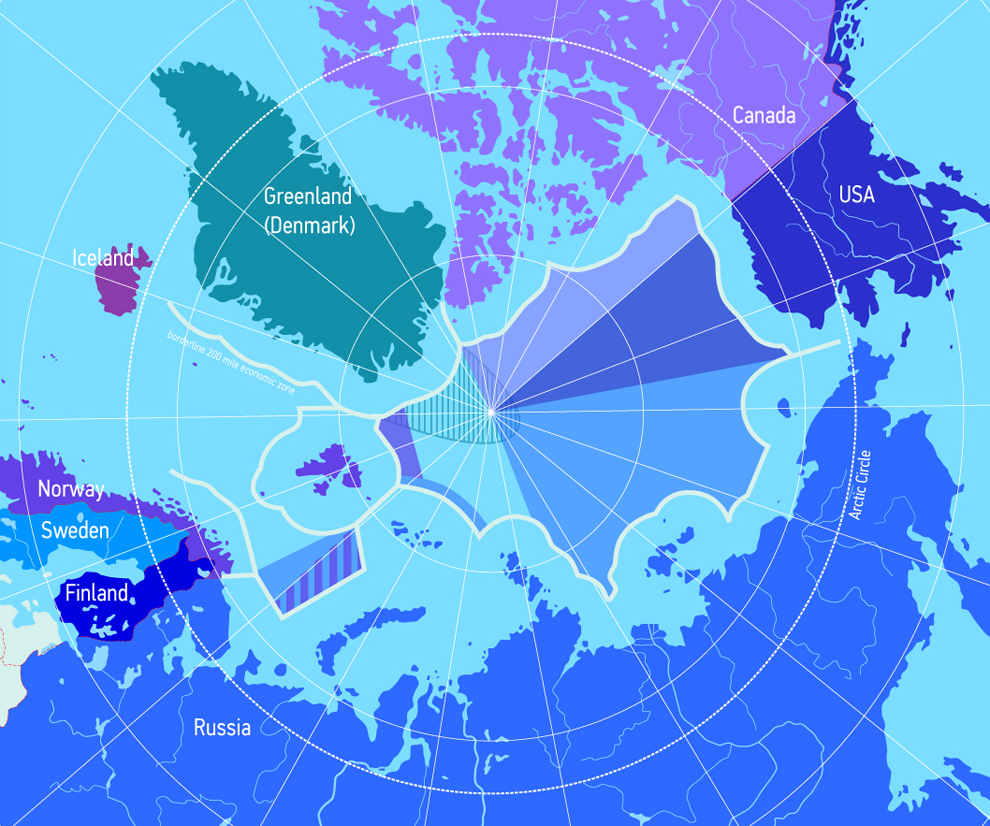

With the continued melting of polar ice-which will enlarge high northern international waters-and the near inevitability of expanded navigation and offshore development, the geopolitical importance of the Arctic region is growing. At the same time, disputes have intensified between some Arctic states, particularly with respect to overlapping claims to areas of the northern seafloor. International "soft laws" such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the U.N. Fish Stocks Agreement, and the regulatory framework of the International Maritime Organization provide arenas for resolving some conflicts. Nonetheless, some experts argue that the existing system is insufficient to cope with the considerable challenges facing the Arctic in the decades to come. Both within and outside of the region, pressure is building for a stronger, more comprehensive framework for cooperative management in the Far North.